Sub-.27: Where The Action Is

by Wayne van Zwoll

Fast and flat sells now. It did 100 years ago. What’s different?

“THE MOST WONDERFUL CARTRIDGE ever developed.” That’s what Roy Chapman Andrews said of the .250 Savage. This intrepid leader of expeditions for the American Museum of Natural History could have used any cartridge. The .30-06, for example. Before the Great War the .30-30 had dispelled the notion that bore diameter defined killing effect; the ’06 had added an exclamation point. But Andrews chose a speedy new quarter-bore developed by Charles Newton. Bullets from the .250/3000 Savage flew faster than those from the .30-06. At 87 and 100 grains, the slender .25s were considerably lighter, but they seemed to kill all out of proportion to their weight. The ammo fit short-action magazines, specifically the Savage 1899’s.

High-speed bullets haven’t lost their shine. You could say the sun has set on .25s; but that would be a short view, given the surge of hot 7mms decades after U.S. hunters all but dismissed the 7×57 – and the recent rush to 6.5s as if .264 bullets were a new thing. The waists of .257 bullets and 6.5s differ little!

Both 7mm and 6.5mm cartridges date to the development of smokeless powder near the close of the 19th century. At that time, armies the world over edged away from thick, heavy bullets driven at a lope by black powder to missiles galloping off ahead of smokeless. The .303 British, with a .311 bullet, arrived in 1888. Germany settled on the 7.92mm (8mm) Mauser that year, with a .318 bullet (the .323 “JS” bullet appeared in 1905). The U.S. went with the .30-40 Krag in ’92, the .30-03 in 1903, the .30-06 in ’06. Other countries chose 6.5s: the 6.5×52 Italian (1891), 6.5×55 Swedish (1894) and 6.5 Arisaka (Japan, in 1897). Holland, Greece and Portugal issued 6.5mm rifles. U.S. infantry would use .30-bore rounds through both world wars, the Korean conflict and Vietnam. It’s possible 8mm and 6.5mm cartridges would have fared better in the U.S. hunting market had their resumes not included a stint with Axis powers.

Early on, hunters favored 6.5s that mirrored military rounds. Explorer Frederick Courtney Selous and the celebrated W.D.M. Bell used the 6.5×54 Mannlicher-Schoenauer on beasts as big as elephants. Its long solid bullets penetrated pachyderm skulls. Charles Sheldon also liked the 6.5×54, finding it adequate for Alaskan brown bears, sheep and moose. Its flat arc, and trim Mannlicher-Schoenauer 6.5×54 carbines, endeared it to riflemen.

The advent of the .270 Winchester in 1925 hardly helped spread the 6.5 gospel stateside. The .270 outperformed every 6.5mm infantry and commercial round then available. RWS trumped it in 1938 with the 6.5×68 Schuler, on the husky German 8×68 case. It was the pre-war equivalent of Winchester’s .264 Magnum. I once borrowed a 6.5×68 to hunt a Spanish ibex. The ram dropped like a stone 200 yards away, a predictable result.

Despite tides of Swedish military Mausers washing up on North American shores, no commercial 6.5×55 ammunition appeared here until 1991, when Federal started loading it. It’s widely available now. At 2.16 inches, hulls are .15 longer than the .308’s. Original overall length (3.15 inches) exceeds that of the 7×57. In fact, it falls just .1 inch shy of the 7mm Remington Magnum’s! The 6.5×55 prefers a long action, which as easily accepts the faster .270. Initially loaded with 156-grain round-nose bullets at 2,378 ft/sec (for rifles with one-in-7.87 rifling) the 6.5×55 hewed for years to breech pressures of 45,000 psi. It can drive modern 140-grain bullets to 2,800 ft/sec from stout rifles like the Winchester 70 and Ruger 77.

The first high-octane 6.5 not buried by the dust of history was fashioned by the man who gave us the first quick, short .25. Charles Newton was born in Delevan, New York in 1870. At age 16 he left the family farm. After a brief stint as a teacher, six years in the National Guard and admission to the state bar, he abandoned a law practice to design cartridges. From 1909 to 1912 Newton focused on the likes of the .25 Special and 7mm/06 – predecessors to the .25-06 and .280 Remington. Then he came up with the .256 Newton, its 129-grain .264 bullet clocking 2,760 ft/sec. Head and rim matched those of the .30-06, but the 2.46-inch case was shorter. It was not short enough for the 99 Savage, however, so Newton followed with the .250 – which Savage called the .250/3000, for the claimed velocity of 87-grain bullets. Newton, by the way, recommended 100-grain bullets at 2,800 ft/sec.

The .250 met little competition at first. A .25 on the Krag case, by A.O. Neidner and F.J. Sage, stumbled because bolt-actions don’t readily feed rimmed cases. Then Ned Roberts chose the 7×57 for his .25. By 1930 Griffin & Howe was building rifles for the Roberts wildcat. In 1934 Remington adopted the cartridge, changing shoulder angle from Whelen’s advised 15 degrees to 20. E.C., Crossman, who referred to the Roberts as a “super .250,” suggested groove diameter in the name to distinguish it from other 25s.

The mid-length Roberts outperformed the .250 Savage. At 300 yards an 87-grain bullet from the .257 penetrated 1/8-inch steel plate only dented by the .250. Still, the Roberts promised little star power. Like the .250, it was designed to operate at under 48,000 psi (117 bullets clocked just 2,650 ft/sec). And like Newton’s .256, its light bullets didn’t shoot accurately enough for varminters. Warren Page pointed out that the .257 didn’t fit short actions and was hardly a ballistic match for the .270. Jack O’Connor took a sunnier view, predicting that by 1950 the .257’s versatility and light recoil would make it hugely popular. He was wrong. In the mid-1950s, Winchester’s new .243 jetted past both the .250 and the .257 at market.

By that time, various versions of the .25-06 were gaining traction, though oddly enough this fast-stepping round got no commercial blessing until Remington adopted it in 1969! The .270 had the loyalty of big game hunters, and in ‘chuck pastures the .22-250 reached as far as fast with less recoil.

During and after the 1940s P.O. Ackley reduced body taper on commercial rounds and steepened their shoulders to 40 degrees. His .250 Savage Improved showed a velocity bump of 300 ft/sec, beating the factory-loaded Roberts. Ackley and Warren Page also came up with the .25 Souper, a necked-up .243. It trounces the .250 Improved and fits as neatly in short actions. I had to have one. Charlie Sisk barreled my Remington 700 with a 24-inch, 1-in-10 Lilja barrel in .25 Souper. A Hi-Tech Specialties stock, a Timney trigger and a Swarovski 3-9×36 in one-piece Talley mounts completed the 7-pound rifle. Handloads send 87-grain Hornadys at a sizzling 3,335 ft/sec. I get over 3,100 with 100-grain Sierras and Noslers. Best news: all shoot inside .85!

If the .25 Souper has a .264 counterpart, it’s the 6.5 Creedmoor, developed at Hornady by senior engineer Dave Emary and introduced in 2009. After tapping competitive shooters for ideas on 1,000-yard cartridges, Dave necked the .30 T/C hull (another Hornady round) to .264. The compact case enabled him to use long, ballistically efficient bullets without exceeding OAL limits imposed by short actions. Thanks to propellants developed for Hornady Superformance ammo, the Creedmoor is almost as quick as the .270 at the muzzle – and overtakes it downrange! The Creedmoor can handle VLD bullets better than can the more capacious but still short-action .260 Remington, a fine cartridge introduced in 2002. It has struggled to emerge from the shade of its popular predecessor the 7mm-08.

Shortly after the Creedmoor’s debut, Todd Seyfert at Magnum Research shipped me a rifle – a 700 Remington so chambered. Its carbon-fiber barrel (Krieger stainless core) floated in a GreyBull Precision stock. GreyBull added an arc-specific dial to the 4.5-14x Leupold. Initiated on steel plates to 500 yards, my 129-grain Hornady load claimed a coyote at 250 – then an elk farther than I’d ever shot an elk. I used the Creedmoor later on deer and South African antelopes. A bit over-matched by a heavy bull eland, this short 6.5 impressed me at every turn. Its 140-grain bullets ably resist drift, holding velocity and energy in a miserly grip downrange. The rifles I’ve used have delivered uniformly tight groups with every load.

The enthusiastic welcome given the Creedmoor is in stark contrast to the reception Winchester’s .264 Magnum received in 1959. Announced as a long-range wonder, it was said to kick 100-grain bullets out at 3,700 ft/sec, 140s at 3,200. But the .243 was more civil, and it too was lethal on animals you’d shoot with 100-grain bullets. While 140s killed bigger ungulates at distance, so did the gentler .270 with 150s. Remington sealed the .264’s fate with the 1962 debut of its 7mm Magnum, cleverly sold as an all-around cartridge for mountain and plain. Its 150- and 175-grain loads kept company with .30 magnums, not the .243 – though its case was almost identical to the .264’s and its bullets just .020 bigger! Hunters bought the message that here was a deer/elk round that shot flat as a .300 but kicked like an ’06.

I’ve taken big game with the .264 Winchester, and used a GreyBull rifle firing VLD handloads to reach a bicycle-size plate hung a measured mile from a bald ridge. Tough task, that one! A twitch of the mirage, a blip of pulse in my sling, sent that shot astray. When at last, through his spotting scope, my pal saw a wink of sun on shivering steel, I quit.

Remington thought a shorter belted 6.5 worth a try, and from 1965 to 1971 manufactured Model 600 and 660 carbines chambered to the .308-length 6.5 and .350 Remington Magnums. Neither sold well. Ballistically, the 6.5 Remington Magnum matches the .270. So does the 6.5/284, on the .284 Winchester hull. First a wildcat favored by long-range marksmen, the 6.5/284 is now commercially loaded. It’s best in long actions, with bullets of high ballistic coefficient seated out. Melvin Forbes designed his M20 Ultra Light Arms action for such mid-length cartridges. I once used a Savage/E.R. Shaw rifle in 6.5/284 to nail an Idaho elk at 290 yards. The 140-grain Partition dropped it instantly.

Count on the 6.5/06 (now legitimized as the 6.5/06 A-Square) to fly as flat, hit as hard.

Roy Weatherby probed quarter-bore possibilities early on, with his .257 Magnum, introduced in 1944. This lightning-quick .25 remained one of Roy’s favorite hunting rounds. Not until this year did the company revisit the sub-.270 arena – at least for big game hunters.

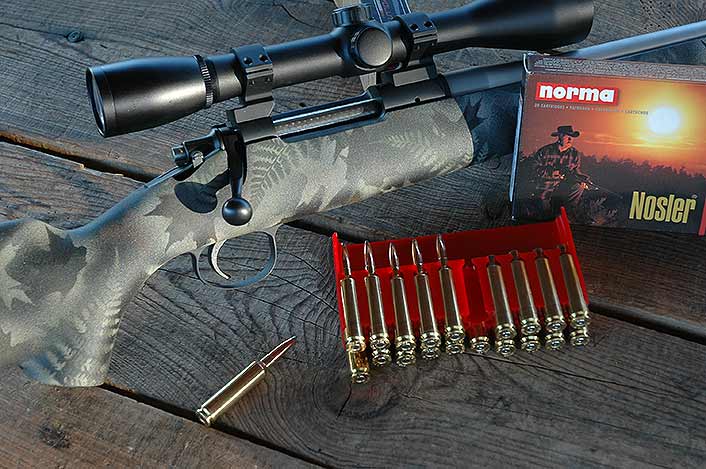

Weatherby may have gotten a nudge from development of the .26 Nosler on the .404 Jeffery hull. With a loaded measure of 3.34 inch, Nosler’s .26 fits a .30-06-length action. Its 35-degree shoulder is set well forward, for a big fuel tank. At chart speeds of 3,400 ft/sec for 129-grain LR AccuBonds and 3,300 for 140 Partitions, the .26 Nosler carries a ton of energy nearly a quarter mile. My handloads for the .26 drive 120-grain Ballistic Tips at 3,700 ft/sec and match factory claims with 129s and 140s.

Loath to be outdone, the Weatherby crew reached back several decades to a wildcat developed by Paul Wright of Silver City, New Mexico for 1,000-yard competition. Gray-haired shooters may remember the 6.5/300 Wright-Hoyer. It’s the same round. Alex Hoyer ran a gun-shop in Mifflintown, Pennsylvania. He built several rifles for the cartridge.

The newest Weatherby Magnum is indeed the 6.5-300. You can get it in Mark V Magnum rifles, with 1-in-8- twist bores for leggy pointed bullets that excel at distance. It’s faster spin than listed for the 139-grain Norma match bullets Wright used. Pick the AccuMark, Arroyo, Outfitter, TerraMark, or 5 3/4-pound Ultra Lightweight Mark V. “We’ve not just added a cartridge to the line,” said Adam Weatherby, now Executive VP and COO. “For 2016 all Mark Vs have been upgraded.” Criterion barrels are lapped. Walnut and hand-laminated synthetic stocks are slimmer in grip and forend. There’s a modest palm swell. Synthetic stocks still boast a full-length rail. A new LXX trigger (for the firm’s 70th year) has a wider face, adjusts down to 2.5 pounds. And now Weatherby guarantees sub-minute accuracy from all Mark Vs.

On a recent visit to the company’s Paso Robles, California factory I watched 6.5-300 Magnums in production. There’s no way to make rifle manufacture hike a reader’s pulse, so I won’t try. The project took most of a day. After primary CNC work, the crew bead-blasted the fluted, stainless barrels and roll-marked them, then torqued them to receivers, endowed bolts with serial numbers, installed triggers and bolt sleeves, checked headspace and fired proof rounds that stiffened bolt lift and left bright ejector marks on case heads. They checked headspace again, polished bolt bodies and adjusted triggers. Bluing imparted a rich, dark finish to receivers and bolt components. Glass bedding into the new stocks was the final step before accuracy tests on Weatherby’s indoor range. The target, 100 yards into the tunnel, has electronic sensors that deliver strikes to a grid on a computer screen at your elbow.

“Help yourself,” said a seasoned staff shooter, handing me one of the newly minted 6.5-300s. Of course, I managed to bungle my first attempts at a tight group. A bore-cleaning over lunch helped me put three 127-grain Barnes LRXs into a .70-inch knot. After 36 shop operations with 33 components, this new Mark V was an accurate, smooth-functioning unit! Incidentally, all 6.5-300 loads offered by Weatherby are assembled at the Paso Robles headquarters, not at Norma, which loads other ammo for the company. Here’s current ballistic data (arc for a 100-yard zero):

| 127-grain Barnes LRX | 200 yds. | 400 yds. | 600 yds. | 800 yds. | 1,000 yds. |

| Velocity, ft/sec | 3099 | 2706 | 2347 | 2015 | 1740 |

| Energy, ft-lbs | 2707 | 2065 | 1553 | 1145 | 828 |

| Arc, inches | -1.7 | -16.4 | -50.3 | -109.6 | -203.6 |

| 130-grain Swift Scirocco II | 200 yds. | 400 yds. | 600 yds. | 800 yds. | 1,000 yds. |

| Velocity, ft/sec | 3084 | 2726 | 2394 | 2087 | 1804 |

| Energy, ft-lbs | 2746 | 2145 | 1655 | 1257 | 939 |

| Arc, inches | -1.7 | -16.7 | -50.4 | -108.6 | -199.0 |

| 140-grain Swift A-Frame | 200 yds. | 400 yds. | 600 yds. | 800 yds. | 1,000 yds. |

| Velocity, ft/sec | 2866 | 2394 | 1970 | 1597 | 1293 |

| Energy, ft-lbs | 2552 | 1781 | 1206 | 793 | 520 |

| Arc, inches | -2.0 | -19.4 | -60.3 | -135.1 | -260.4 |

At distance the 6.5-300 shines. Factory-loaded 127-grain Barnes bullets clock 3,537 ft/sec from my rifle and reach 300 yards traveling over 2,900! At 500 they match the muzzle velocity of 156-grain bullets from a 6.5×55! Point-blank range on a 5-inch target: 305 yards. So if you zero a 6.5-300 Mark V near 200 yards, bullets will hit within 2 1/2 vertical inches of point of aim to 305. They bring 3,100 ft-lbs of energy to 100 yards, 1,800 to 500 and retain 1,000 ft-lbs until near the 900-yard mark, where the bullets still zip by at 1,900 ft/sec. That’s about how fast early smokeless loads drove .30-30 softpoints out the muzzle!

High speed doesn’t beget efficiency. Even the .25-06 case holds a lot of powder, given the area of its bullet base. But performance counts. F-22 fighters aren’t fuel-efficient either. Is the 6.5-300 Weatherby – with other hot .25s and 6.5s – a barrel-burner? In competitive shooting, constant fire under the press of time can indeed eat throats. Ditto hot-barrel shooting over prairie dog towns. But on big game hunts shots are infrequent. Few hunters who criticize “over-bore capacity” cartridges have actually worn out barrels.

I’m still sweet on the .250 Savage and the .25 Souper. I killed my biggest whitetail with a .25-06. The 6.5 Creedmoor is a superb cartridge – better even than my 6.5 Redding, a wildcat predecessor to the .260. But sometimes flatter flight and a deadlier payload justify a louder report, sharper recoil. Despite its dismal reputation, I like the .264 Winchester Magnum, which my handloads (with IMR 7828) can stoke to over 3,300 ft/sec with 140-grain bullets. The .257 Weatherby is sudden death on distant deer. Nosler’s .26 and the 6.5-300 Weatherby certainly offer more speed and energy, and burn more powder, than thought necessary when Charles Newton came up with the .250 Savage and his .256. But neither bullets nor optics of that day could tap a higher level of performance – the performance many shooters now demand.

Wayne van Zwoll has published 16 books and roughly 3,000 magazine articles on firearms and hunting. Five of his most popular books are: Shooter’s Bible Guide to Rifle Ballistics ($20), Shooter’s Bible Guide to Handloading ($20), Mastering Mule Deer ($25), Mastering the Art of Long-Range Shooting ($30) and Gun Digest Shooter’s Guide to Rifles ($20). Limited numbers are available, autographed, from Wayne at 2610 Highland Drive, Bridgeport WA 98813. Please add $4 shipping.

Stay Connected

- Got a Break in the Montana Missouri Breaks

- It Took Six Days but We Finally Slipped One Past the Bears and Wolves

- No Mule Deer This Fall – Whitetail TOAD!

- An Accounting of Four Idaho Bulls (Elk)

- Arizona Deer Hunt 2019: Good Times with Great Guys

- Caught a Hornady 143 ELDX Last Night

- Cookie’s 2019 Mule Deer Photo Run

- Let’s See Some Really Big Deer

- Alaskan Moose Hunt Success!

- Take a Mauser Hunting: An Important Message From The Mauser Rescue Society!

- Welcome 16 Gauge Reloaders! Check In Here.

- Off-Hand Rifle Shooting – EXPERT Advice

- BOWHUNTING: A Wide One!